Testing SQL

SQL isn’t easy to test. Unlike most programming languages, there’s no testing framework you can use out of the box. To get around this, users will typically test their SQL queries against production data and spot check the results, or rely on experienced coworkers to review the code. You can get by with this approach in some cases, but as SQL queries evolve over time or grow in complexity, the possibility for uncaught errors rises significantly.

In this post, I’ll demonstrate one method for testing SQL through the use of mock data. This approach has served me well for doing one-off validation of more complex queries, and in continuous integration tests for any production deployments that rely on SQL to perform nontrivial logic.

Mocking Data

The premise behind software testing is to run your code against a set of pre-defined inputs and compare the behaviour (or output) of the code to your expectation. For SQL code, the inputs are the tables in your database. So in order to run our SQL code against some pre-defined inputs, we need to create some tables, or table-like structures, that are filled with test data. The SQL query can then run against these “mocked tables”, and the corresponding output can be validated.

Most relational databases (Postgres, Redshift, Snowflake, etc.) support the creation of temporary tables, which persist for the length of a session.

CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE users (

id INTEGER,

first_name VARCHAR,

last_name VARCHAR

);

INSERT INTO users VALUES(1, 'foo', 'bar');

INSERT INTO users VALUES(2, 'bar', 'baz');

However, this is not implemented in all databases. BigQuery only allows for the creation of temporary tables through their scripting feature1, and Trino (formerly known as Presto) does not support them at all. To get around this, we can rely on common table expressions (CTE’s) which are supported in all SQL-compliant databases.

The same temporary table I showed above can be written as a CTE2:

WITH

users AS (

SELECT * FROM (

VALUES

(1, 'foo', 'bar'),

(2, 'bar', 'baz')

) AS t (id, first_name, last_name)

)

One-off testing

The mock data approach can easily & quickly be applied to perform some one-off testing of complex SQL logic, or to understand the behaviour of a certain SQL function.

For example, my team was recently working on prototyping a new data model in SQL that would allow us to identify what e-commerce orders could be eligible for duties. The eligibility logic was something like:

- At least one of the items in the order is shipped across country borders

- This does not apply to intra-EU shipments, so an order shipped from France to Germany would not be charged duties. But orders can be fulfilled from multiple locations, so an order shipped from France & Canada to Germany could be charged duties.

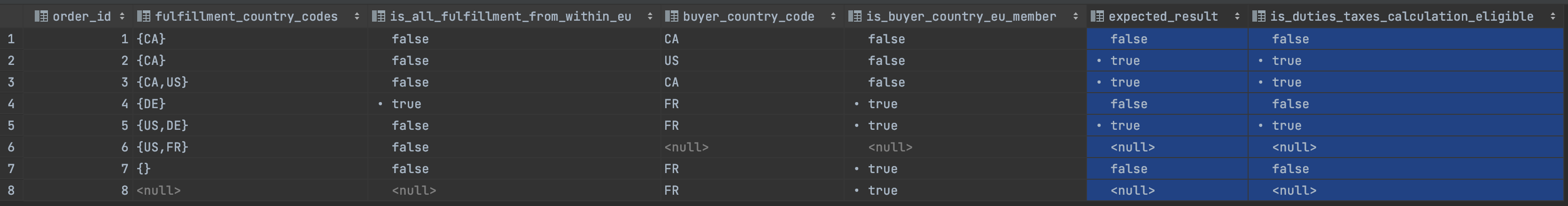

The SQL query for this ended up being quite complex, as we had to aggregate all the fulfillment location countries into an array, get the buyer shipping address country, and then lookup which of those countries were EU members for every order. To ensure our logic was correctly covering all corner cases, we ended up quickly validating it using mocked data. Our final test looked something like this:

-- Run in Trino (Presto)

WITH

sample_data AS (

SELECT * FROM (

VALUES

-- Domestic fulfillment

(1, ARRAY['CA'], False, 'CA', False, False),

-- Cross border fulfillment

(2, ARRAY['CA'], False, 'US', False, True),

-- Partial cross border fulfillment

(3, ARRAY['CA', 'US'], False, 'CA', False, True),

-- Cross burder fulfillment, intra EU

(4, ARRAY['DE'], True, 'FR', True, False),

-- Partial cross border fulfillment, intra EU

(5, ARRAY['US', 'DE'], False, 'FR', True, True),

-- missing the buyer country code

(6, ARRAY['US', 'FR'], False, Null, Null, Null),

-- no fulfillment countries that required shipping

(7, ARRAY[], Null, 'FR', True, False),

-- missing fulfillment data for the order

(8, Null, Null, 'FR', True, Null)

) AS t (

order_id,

fulfillment_country_codes,

is_all_fulfillment_from_within_eu,

buyer_country_code,

is_buyer_country_eu_member,

expected_result

)

)

SELECT

*,

CASE

-- If buyer country or fulfillment countries are missing,

WHEN buyer_country_code IS NULL OR fulfillment_country_codes IS NULL THEN NULL

WHEN

-- There is at least 1 fulfillment country that is different than the buyer country

CARDINALITY(ARRAY_EXCEPT(fulfillment_country_codes, ARRAY[buyer_country_code])) > 0

-- And the fulfillment is not entirely contained within the EU

AND NOT (

is_buyer_country_eu_member

AND is_all_fulfillment_from_within_eu

)

THEN TRUE

ELSE False

END AS is_duties_eligible

FROM

sample_data

ORDER BY order_id

By running our final logic against some mock data, we were able to validate that it was outputting the expected result across all test cases:

Continuous testing for production deployments

The same mock data approach can be leveraged for continuous integration testing of SQL in production deployments.

In one of my first jobs I was responsible for a batch machine learning model deployment. The first step in the model pipeline was to run a set of SQL queries with some basic transformations, read those results into memory, and then perform the remaining transformations, feature engineering and model scoring (predictions) in Python. Using the mock data approach outlined above, I implemented an end to end integration test where the SQL code was run against temporary tables loaded with test data, and the results were fed through the rest of the pipeline and validated against expectations.

At Shopify, we’ve built our own SQL data modelling framework on top of dbt. In addition to the runtime testing that dbt provides (think uniqueness or null value checks on the final dataset), we’ve also built in functionality for unit testing our data models (SQL code) against mock data.

Both of these applications followed a similar approach using Jinja, which I’ll demonstrate below.

Example SQL integration test

Let’s pretend we have a Python job that is responsible for forecasting transaction volumes in each country. The input dataset required for the job is produced from a SQL script:

SELECT

DATE_PART('doy', t.processed_at) AS day_of_year,

u.country,

SUM(amount) AS trxn_volume

FROM

transactions AS t

INNER JOIN users AS u

ON t.user_id=u.id

GROUP BY 1,2

ORDER BY 1,2

In order to test this query, we’d need to create some mock data for the transactions and users tables, and then have our SQL code read from these mocked tables instead of the actual production ones. To dynamically point our query to different tables, we’ll leverage the Jinja templating engine.

SELECT

DATE_PART('doy', t.processed_at) AS day_of_year,

u.country,

SUM(amount) AS trxn_volume

FROM

{{ transactions }} AS t

INNER JOIN {{ users }} AS u

ON t.user_id=u.id

GROUP BY 1,2

ORDER BY 1,2

When the code is being run in “production” mode, {{ transactions }} and {{ users }} will be rendered by Jinja with the actual production table names. In “test” mode, we’ll dynamically generate CTEs containing our test data, and have {{ transactions }} and {{ users }} point to those. The rendered SQL in “test” mode would look something like this:

WITH

test_transactions AS (

SELECT * FROM (

VALUES

(1, 1, 15.0, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-01 12:05'),

(2, 1, 10.49, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-01 12:10'),

(3, 1, -10.49, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-01 12:15'),

(4, 2, 25.99, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-02 15:25'),

(5, 2, 5.45, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-05 14:01'),

(6, 2, 50.5, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-07 03:45'),

(7, 3, 49.5, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-07 22:45')

) AS t (id,user_id,amount,processed_at)

),

test_users AS (

SELECT * FROM (

VALUES

(1, 'US'),

(2, 'CA'),

(3, 'CA')

) AS t (id,country)

),

results AS (

SELECT

DATE_PART('doy', t.processed_at) AS day_of_year,

u.country,

SUM(amount) AS trxn_volume

FROM

test_transactions AS t

INNER JOIN test_users AS u

ON t.user_id=u.id

GROUP BY 1,2

ORDER BY 1,2

)

SELECT

*

FROM

results

To accomplish this in Python, you could store your SQL template & test data like this:

# Jinja variable name -> production table name mapping

TABLE_XREF = {

'transactions': 'transactions',

'users': 'users',

}

BASE_SQL = """

WITH

results AS (

SELECT

DATE_PART('doy', t.processed_at) AS day_of_year,

u.country,

SUM(amount) AS trxn_volume

FROM

{{ transactions }} AS t

INNER JOIN {{ users }} AS u

ON t.user_id=u.id

GROUP BY 1,2

ORDER BY 1,2

)

SELECT

*

FROM

results

"""

TEST_DATA = {

'users': {

"column_names": ['id', 'country'],

"values": [

"(1, 'US')",

"(2, 'CA')",

"(3, 'CA')",

]

},

'transactions': {

"column_names": ['id', 'user_id', 'amount', 'processed_at'],

"values": [

"(1, 1, 15.0, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-01 12:05')",

"(2, 1, 10.49, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-01 12:10')",

"(3, 1, -10.49, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-01 12:15')",

"(4, 2, 25.99, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-02 15:25')",

"(5, 2, 5.45, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-05 14:01')",

"(6, 2, 50.5, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-07 03:45')",

"(7, 3, 49.5, TIMESTAMP'2020-01-07 22:45')",

]

}

}

And then whenever you are in “test” mode, you can dynamically build & inject the CTEs above the final results CTE with these functions:

def build_cte(table_ref, table_name):

values = ",\n".join(TEST_DATA[table_ref]['values'])

column_names = ",".join(TEST_DATA[table_ref]['column_names'])

cte = f"""

{table_name} AS (

SELECT * FROM (

VALUES \n{values}

) AS t ({column_names})

),

"""

return cte

def inject_cte(sql, cte):

"""

Add the CTE directly after the WITH statement.

"""

sql_parts = sql.split('WITH')

return f"WITH{cte}" + sql_parts[1]

After declaring your expected results, you can run execute the SQL with the test data, read it into a dataframe, and then compare it to the expected results:

EXPECTED_RESULTS = {

'day_of_year': [1, 2, 5, 7],

'country': ['US', 'CA', 'CA', 'CA'],

'trxn_volume': [15, 25.99, 5.45, 100]

}

def render_sql(mode):

sql_template = Template(BASE_SQL)

ast = Environment().parse(BASE_SQL)

jinja_table_refs = meta.find_undeclared_variables(ast)

table_prefix = ''

if mode == 'test':

# consider generating a random string in case there

# could actually be a table named test_users or test_transactions

table_prefix = 'test_'

# map Jinja table reference to actual table (or CTE) name

table_mapping = {

table_ref: f"{table_prefix}{TABLE_XREF[table_ref]}"

for table_ref in jinja_table_refs

}

sql = sql_template.render(**table_mapping)

if mode == 'test':

# create & inject the CTEs containing fake data into the SQL

for table_ref, table_name in table_mapping.items():

cte = build_cte(table_ref, table_name)

sql = inject_cte(sql, cte)

return sql

sql = render_sql('test')

print(f"Executing SQL:\n{sql}")

actual_df = psql.read_sql(sql, CONNECTION)

expected_df = pd.DataFrame(EXPECTED_RESULTS)

print(f'Actual dataframe is:\n {actual_df}\nExpected dataframe is:\n{expected_df}')

assert_frame_equal(actual_df, expected_df, check_dtype=False)

print('Matchy matchy ✨!')

You can see the full, working example of this process in this Python file gist.

Notes

1 See this stack overflow discussion.

2 In BigQuery, the syntax is slightly different:

WITH

users AS (

SELECT *

FROM

UNNEST(

ARRAY<STRUCT<id INT64, first_name STRING, last_name STRING>>[

(1, 'foo', 'bar'),

(2, 'bar', 'baz')

]

)

)