Up & running with Great Expectations

- hello, great expectations

- Case Study: Expectations for Apartment Listings

- Deploying in Production

- Closing Thoughts

Data issues often go undetected but can wreak havoc on downstream models and dashboards once discovered. To combat this, data professionals should invest in automated data pipeline tests, which continuously validate data against a set of expectations. In the inaugural post; Down with Pipeline debt, the Python package great-expectations was announced as a powerful, open-source tool to help with this exact problem. In this post, I’ll dive into the package and show how you can easily get a set of data pipeline tests up & running in production. I’ll also highlight some ways I’m using the package to monitor a live application out in the wild.

hello, great expectations

Before going in-depth, let’s start with a motivating example to show how great-expectations, henceforth referred to as “ge”, can be used.

import great_expectations as ge

# Build up expectations on a representative sample of data and save them to disk

train = ge.read_csv("data/my_existing_batch_of_data.csv")

train.expect_column_values_to_not_be_null("id")

train.save_expectation_suite("my_expectations.json")

# Load in a new batch of data and test it against our expectations

test = ge.read_csv("data/my_new_batch_of_data.csv")

validation_results = test.validate(expectation_suite="my_expectations.json")

# Take action based on the results

if validation_results["success"]:

print ("giddy up!")

else:

raise Exception("oh shit.")

What’s going on here?

1) We load in an existing batch of data and log our expectations for how the data should behave

- This process is usually done once, and in an interactive environment, like jupyter. It requires lots of trial and error as you learn new things about your data and encode all your beliefs for how future data should behave.

- Under the hood, the

ge.read_csv()method is usingpandasto load a dataset from disk. Alternatively, a ge dataset can be initialized directly from an existing pandas dataset withge.from_pandas(my_pandas_df). Any subsequent expectations we create and run will be executed as operations against this underlying pandas dataframe. - We explicitly state that we expect all values in the

idcolumn to be non-null. This is a very straightforward example, and something that can usually be handled by database schema constraints. Nonetheless, it illustrates the simple and declarative nature of ge. There are a whole host of other, more powerful expectations listed here. - We save our suite of expectations to disk. Here’s what

my_expectations.jsonlooks like:

{

"data_asset_type": "Dataset",

"expectation_suite_name": "default",

"expectations": [

{

"expectation_type": "expect_column_values_to_not_be_null",

"kwargs": {

"column": "id"

},

"meta": {}

}

],

"meta": {

"great_expectations.__version__": "0.9.8"

}

}

2) We load in a new batch of data and validate it against our expectations

- A new batch of data arrives, and we want to test it against our expectations.

- We load in the data with the same API we saw previously, and call the

validatemethod to test the new data against all the expectations stored inmy_expectations.json.

3) We check whether the new batch of data met all our expectations

- In the event it does not, we will raise an exception.

- It is worth pointing out that you can exercise many different options here. Rather than raising an exception, you could instead continue your process and fire off a slack notification prompting a team member to investigate.

- Alternatively, you could create multiple sets of expectation suites: one that will cause warnings to be issued when expectations are not met, and another which will halt the pipeline execution in the event of non-conformance.

- The

validation_resultsobject contains all the information you’d need to perform any type of custom handling based on the results. Here’s what it looks like:

{

"results": [

{

"exception_info": {

"raised_exception": false,

"exception_message": null,

"exception_traceback": null

},

"meta": {},

"result": {

"element_count": 3976,

"unexpected_count": 0,

"unexpected_percent": 0.0,

"partial_unexpected_list": []

},

"success": true,

"expectation_config": {

"kwargs": {

"column": "id"

},

"expectation_type": "expect_column_values_to_not_be_null",

"meta": {}

}

}

],

"meta": {

"great_expectations.__version__": "0.9.8",

"expectation_suite_name": "default",

"run_id": "20200413T182038.187591Z",

"batch_kwargs": {

"ge_batch_id": "79a665d0-7db3-11ea-beb3-88e9fe52e3b3"

},

"batch_markers": {},

"batch_parameters": {}

},

"evaluation_parameters": {},

"statistics": {

"evaluated_expectations": 1,

"successful_expectations": 1,

"unsuccessful_expectations": 0,

"success_percent": 100.0

},

"success": true

}

The example above illustrates the simplicity and true power of ge. With just two lines of Python, you can have a comprehensive set of data quality checks running in production against each new batch of data:

import great_expectations as ge

test = ge.read_csv("data/my_new_batch_of_data.csv")

validation_results = test.validate(expectation_suite="my_expectations.json")

Note: You can find a similar "hello world" example using a SQLAlchemy backend instead of Pandas here.

In my opinion, this should be enough to get you up & running with ge, and hopefully, motivate you to do so. However, if you are interested in going deeper and learning more about what ge has to offer, read on.

Case Study: Expectations for Apartment Listings

domi is a side project I threw together, primarily for a learning experience. In a nutshell, it’s an application that pulls listings from various apartment sites and sends users a custom feed of new listings in slack. domi is a data-intensive application, where data integrity is core to the product offering. Given this, it was imperative for me to have a set of data tests running on each new batch of data to ensure the data pipelines were functioning as expected. In the sections below, I’ll walk you through a subset of the expectations I’ve been using in order to show you an example of ge out in the wild and explore more of the package’s functionality.

Great Expectations Backends

Before we move to discussing the expectations used for domi, a quick sidebar to ge’s supported backends. In the section above, the code snippets I showed leveraged ge’s PandasDataset. When choosing this option, your entire dataset must be read into memory, and subsequent validations will be run against that Pandas dataframe. This is a great option for most workflows, particularly due to the popularity of Pandas and the widespread familiarity with its API.

ge also supports two other computational backends, a SparkDataset and a SqlAlchemyDataset. With the Spark dataset, you can have your data & ge validations processed in a Spark cluster. With the SQLAlchemy dataset, the ge validations will get automatically compiled and run as SQL queries, meaning your database acts as the computational workhorse.

For my ge deployment with domi, I chose to use the SqlAlchemyDataset. Doing so allowed me to have a lightweight deployment, as the validations are all executed in the database where the data lives. Note, you should be thoughtful when doing this as having a bunch of validations (queries) running in your database may inadvertently affect your application performance. I was comfortable with this trade off since I (a) have virtually no users and (b) have my expectations running in the middle of the night.

Basic Checks

The process of authoring expectations requires you to build up an in-depth understanding of your data, and the associated system that produces it. This may seem arduous, but I can assure you that the long term payoff is worth it.

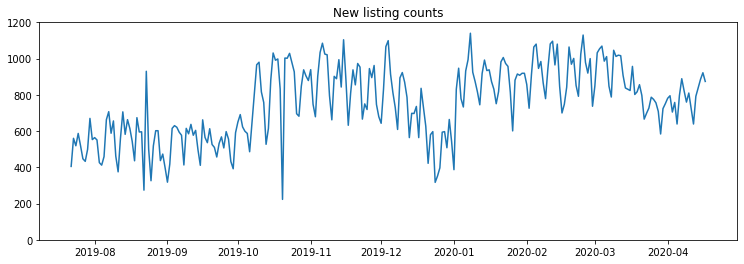

In order for domi to function, it needs a fresh feed of new listings coming in each day. To validate this process is working as expected, we can implement a simple check for a minimum number of listings coming in each day.

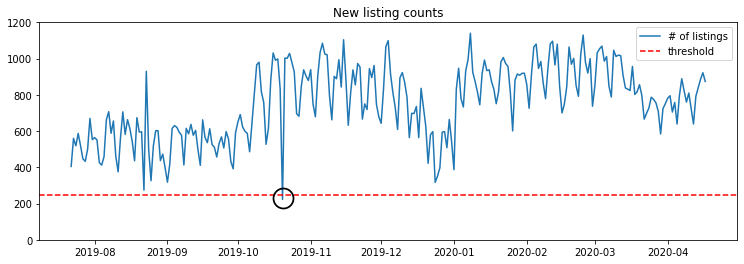

Looking at historical data, data practioners can use their judgement to select threshold values to enforce. When creating expectations retro-actively, you can easily backtest them to see how often your new batches would be in violation. For this use case, I selected the minimum number of daily listings to be 250.

You can see this constraint has been met for most of the application’s history, with the exception of a single day in October 2019 where some of the application’s batch jobs were failing. Here’s how we can begin logging these expectations:

"""

Typically run once, in an interactive environment like Jupyter Lab

"""

import os

from great_expectations.dataset import SqlAlchemyDataset

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

# Manually establish database connection and create dataset.

# In a future post, I will show how ge can automatically take

# care of this connection setup

db_string = "postgres://{user}:{password}@{host}:{port}/{dbname}".format(

user=os.environ["DB_USER"],

password=os.environ["DB_PASSWORD"],

port=os.environ["DB_PORT"],

dbname=os.environ["DB_DBNAME"],

host=os.environ["DB_HOST"],

)

db_engine = create_engine(db_string)

listings = SqlAlchemyDataset(table_name='listings', engine=db_engine)

# Add our first expectation

listings.expect_table_row_count_to_be_between(min_value=250)

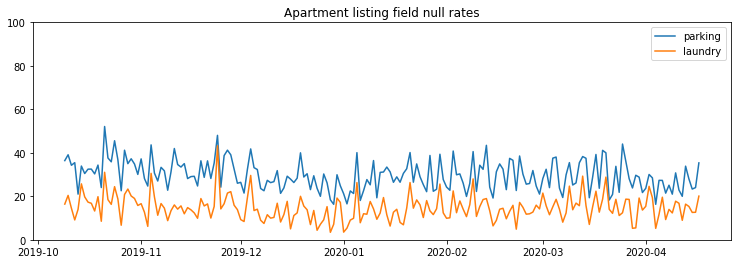

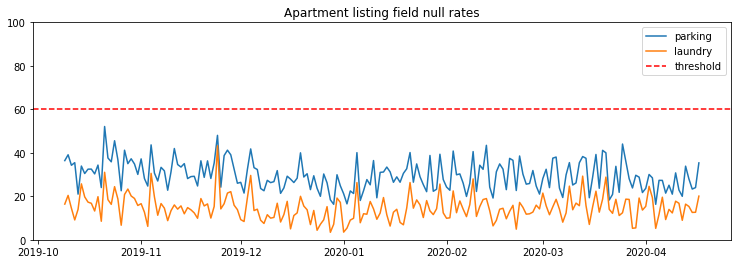

On common apartment sites, listings will have varying metadata as the sites give users flexibility over what information they provide. Below are the daily null rates for two metadata fields; laundry & parking. In this case, a null rate is defined as the % of listings that did not contain the given field.

With webscraping, or more generally, any data extraction methods that are not going through officially supported APIs, extracted data is bound to start misbehaving without warning. For example, a simple change of a <div> element may cause a webscraper to stop capturing a particular piece of information. To protect ourselves against having these changes go un-noticed, we can set some expectations about how often a given field should be null. With the example above, I’ll set a conservative threshold of a maximum null rate of 60%.

We now log these constraints using the expect_column_values_to_not_be_null expectation:

# Add our null rate expectations

listings.expect_column_values_to_not_be_null('parking', mostly=0.4)

listings.expect_column_values_to_not_be_null('laundry', mostly=0.4)

# And finally, save our suite of expectations to disk for future use

listings.save_expectation_suite('listings_expectations.json')

All of ge’s column level expectations come with the option to specify a mostly parameter. mostly allows some wiggle room when evaluating expectations. From the docs:

As long as mostly percent of rows evaluate to True, the expectation returns

“success”: True.

Therefore, we set the mostly parameter to be 0.4, indicating that as long as at least 40% of the rows are not null, our expectation will pass.

With our process above, you can see that we created the expectation suite using the entire listings table. Going forwards, we’ll only want to be validating the new incoming data. For example, validate the last day’s worth of data.To accomplish this, we’ll initialize the SqlAlchemyDataset with a custom query.

query = """

SELECT *

FROM

listings

WHERE

DATE_TRUNC('day', created_at) = CURRENT_DATE - INTERVAL '1' DAY

"""

recent_listings = SqlAlchemyDataset(custom_sql=query, engine=db_engine)

recent_listings.validate(

expectation_suite="listings_expectations.json"

)

if validation_results["success"]:

...

Distributional Checks

One of the trickiest data issues to detect is data drift. Data drift occurs when the underlying distributions in your data begin to change. Unless you are explicitly monitoring these distributions over time, it is unlikely that such changes will be detected. Data drift can have nasty effects on downstream machine learning models that rely on these data as input features. In other situations, having drift go undetected could mean you fail to understand some key change in your business metrics or source systems.

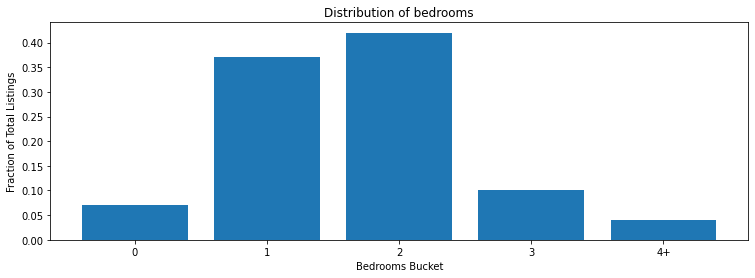

In the apartment hunting world, a common way to categorize listings is by the number of bedrooms. The graph below shows an example distribution of bedroom counts.

Let’s say we want to detect changes in the distribution of bedroom counts. We could be interested in doing this to understand shifts in the market, or potential data issues where users posting the listings are omitting the field. In my case, the field is used as an input to domi’s price rank model, so it’s important for me to be aware of any distribution shifts.

ge comes with an implementation of the Chi-squared test, which is a common test used to compare two categorial variable distributions. Implementing this test is fairly simple. You calculate your expected weights of each category (fractions - see values in graph above) and specify them when creating the expectation.

listings.expect_column_chisquare_test_p_value_to_be_greater_than(

column='bedrooms_bucket',

partition_object={

"values": ['0', '1', '2', '3', '4+'],

"weights": [0.07, 0.37, 0.42, 0.10, 0.04],

},

p=0.05

)

Another important step when creating distributional expectations is backtesting. You’ll want to make sure that the p-value you’ve set is not overly sensitive, and the sample size you test on each day is not too small. This process is outside of the scope of this blog post, but something I hope to cover in the near future.

Extending Great Expectations with Custom Expectations

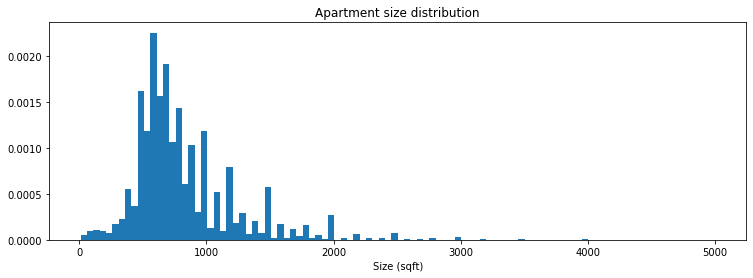

Another input to the price rank model is the apartment size:

Since the apartment size is a continuous variable, we cannot use the Chi-square test (unless we did some custom, manual binning). Instead, ge comes with an implementation of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) test, which can be used to compare two arbitrary, continuous distributions.

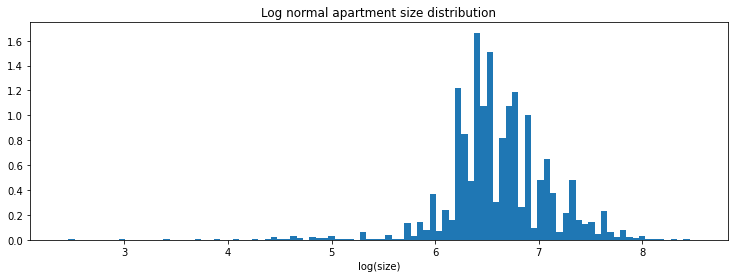

The ge implementation of the K-S test requires us to specify the parameters of the distribution we would like to compare our new data to. In order to do this, we need to provide the parameters of our expected distribution. By visually inspecting the plot above, you can observe that the distribution appears to be log-normal. This can be validated by plotting the log(size), and observing a distribution that looks approximately normal.

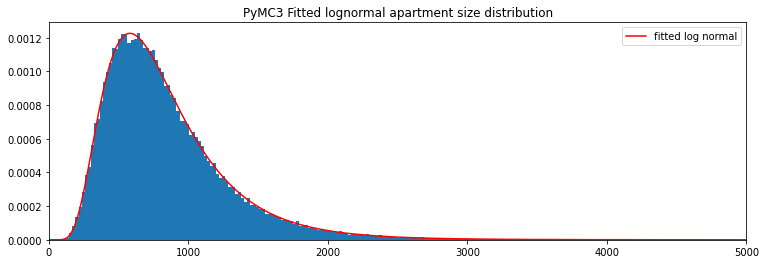

I recently finished Cam Davidson-Pilon’s fantastic introductory book to bayesian methods, so I chose to fit a distribution using PyMC3 to test out what I learned. Alternatively, you can use scipy’s built-in fit methods.

import numpy as np

import pymc3 as pm

import scipy.stats as stats

with pm.Model() as model:

# Specify some wide priors

mu_ = pm.Uniform('mu', 5, 10)

sigma_ = pm.Uniform('sigma', 0, 5)

price = pm.Lognormal('size', mu=mu_, sigma=sigma_, observed=df.sqft)

# Crazy MCMC shit

step = pm.Metropolis()

trace = pm.sample(15000, step=step)

s_ = trace["sigma"][5000:].mean()

scale_ = np.exp(trace["mu"][5000:].mean())

To implement our K-S expectation, we simplify pass in the parameters of our expected distribution.

listings.expect_column_parameterized_distribution_ks_test_p_value_to_be_greater_than(

column='sqft',

distribution='lognorm',

params={

's': s_,

'scale': scale_,

'loc': 0

},

p_value=0.05

)

Unfortunately, this will raise a NotImplementedError since the expectation has only been implemented for the PandasDataset (as of 2020-04-22). But, lucky for us, ge comes with built-in flexibility that allows us to implement our own custom expectations. Using this, I re-created the K-S test for a SqlAlchemyDataset by porting over the original code.

from great_expectations.data_asset import DataAsset

from great_expectations.dataset import SqlAlchemyDataset

import numpy as np

import scipy.stats as stats

import sqlalchemy as sa

class CustomSqlAlchemyDataset(SqlAlchemyDataset):

_data_asset_type = "CustomSqlAlchemyDataset"

@DataAsset.expectation(["column", "distribution", "p_value"])

def expect_column_parameterized_distribution_ks_test_p_value_to_be_greater_than(

self,

column,

distribution,

p_value=0.05,

params=None,

result_format=None,

include_config=True,

catch_exceptions=None,

meta=None

):

if p_value <= 0 or p_value >= 1:

raise ValueError("p_value must be between 0 and 1")

positional_parameters = (params['s'], params['loc'], params['scale'])

rows = self.engine.execute(sa.select([

sa.column(column)

]).select_from(self._table)).fetchall()

column = np.array([col[0] for col in rows])

# K-S Test

ks_result = stats.kstest(column, distribution, args=positional_parameters)

return {

"success": ks_result[1] >= p_value,

"result": {

"observed_value": ks_result[1],

"details": {

"expected_params": params,

"observed_ks_result": ks_result

}

}

}

Now instead of creating our dataset with the built-in SqlAlchemyDataset, we do so with the custom one I just created:

from my_file.custom_sqa_dataset import CustomSqlAlchemyDataset

listings = CustomSqlAlchemyDataset(table_name='listings', engine=db_engine)

# Add now we can successfully create our K-S expectation

listings.expect_column_parameterized_distribution_ks_test_p_value_to_be_greater_than(

column='sqft',

distribution='lognorm',

params={

's': s_,

'scale': scale_,

'loc': 0

},

p_value=0.05

)

Deploying in Production

While expectations are the true workhouse of ge (in my opinion), ge also comes with a lot of other nice abstractions and functionality for supporting the storage, retrieval, and execution of expectations, along with systems for alerting users and storing validation results. Covering all this is outside the scope of this post, as there are whole host of different concepts that would need to be introduced.

At the end of the day, a ge deployment is as simple as executing a script on a schedule that does the following:

- Fetches a new batch of data

- Validates it against the desired expectations suite

- Takes action based on the validation results

I have been running my ge deployment in parallel to my application. For more complex deployments, you could have ge checks running at different steps of your data pipeline. Leveraging the work from above, with some added code for slack alerting, will give you everything you need to execute data quality checks on a daily basis:

import json

import os

from great_expectations.dataset import SqlAlchemyDataset

import requests

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

# 1) Load in a new batch of data

db_string = "postgres://{user}:{password}@{host}:{port}/{dbname}".format(

user=os.environ["DB_USER"],

password=os.environ["DB_PASSWORD"],

port=os.environ["DB_PORT"],

dbname=os.environ["DB_DBNAME"],

host=os.environ["DB_HOST"],

)

db_engine = create_engine(db_string)

query = """

SELECT *

FROM

listings

WHERE

DATE_TRUNC('day', created_at) = CURRENT_DATE - INTERVAL '1' DAY

"""

recent_listings = SqlAlchemyDataset(custom_sql=query, engine=db_engine)

# 2) Validate it against stored expectation suite

validation_results = recent_listings.validate(

expectation_suite="listings_expectations.json"

)

# 3) Take action based on the validation results

if not validation_results["success"]:

num_evaluated = validation_results["statistics"]["evaluated_expectations"]

num_successful = validation_results["statistics"]["successful_expectations"]

validation_results_text = json.dumps(

[result.to_json_dict() for result in validation_results["results"]],

sort_keys=True,

indent=4,

)

slack_data = {

"text": (

f"⚠️ Dataset has failed expecations\n"

f"*Successful Expectations*: `{num_successful}/{num_evaluated}`\n"

f"*Results*: ```\n{validation_results_text}\n```"

)

}

response = requests.post(

os.environ['SLACK_WEBHOOK'],

data=json.dumps(slack_data),

headers={"Content-Type": "application/json"},

)

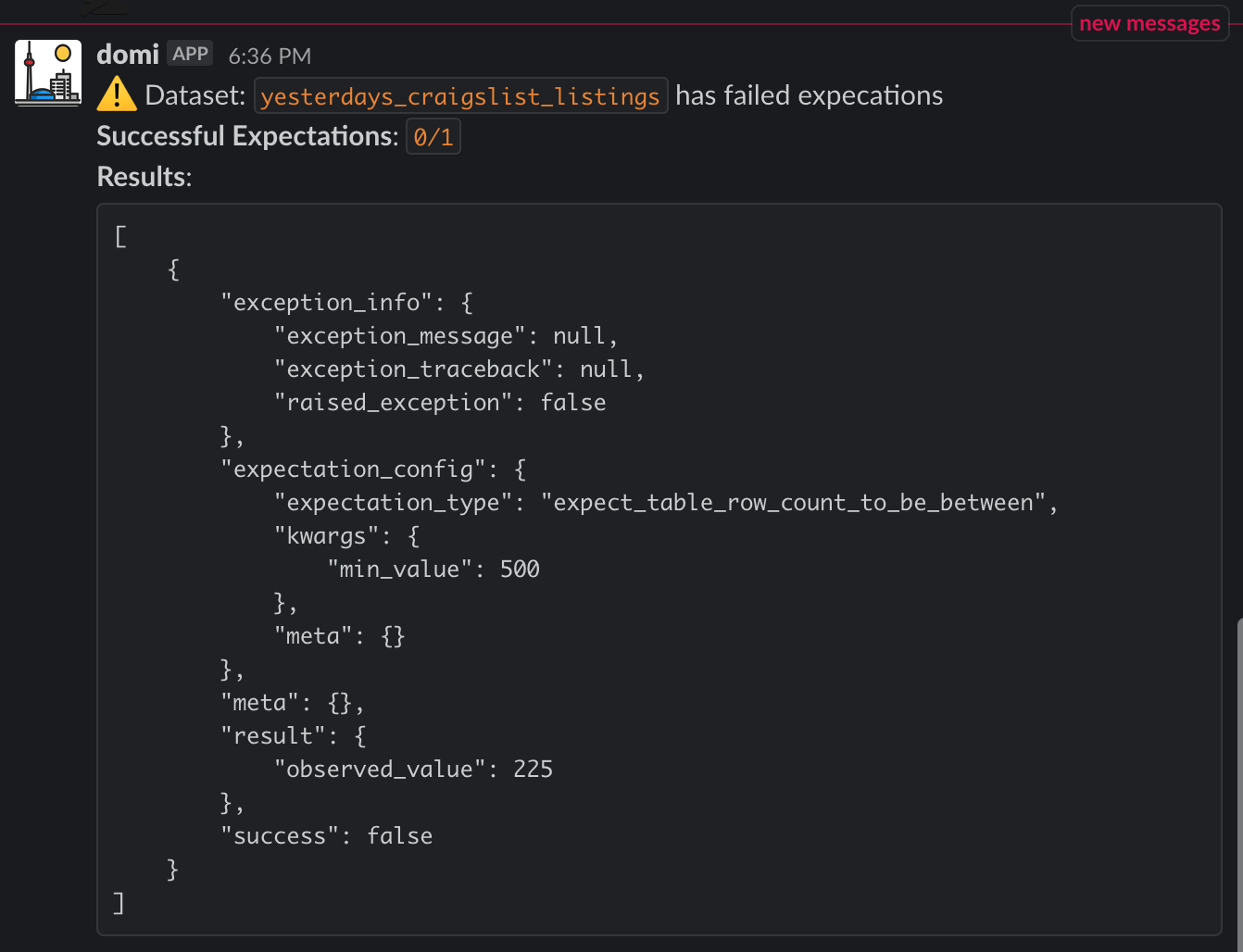

When expectations are violated, you’ll get an alert like this:

You can easily accomplish a ge deployment with a small server and a cron job. For domi, I have been using Zappa to automatically manage and deploy a Lambda (serverless) function that executes a script similar to the one shown above on a regular schedule. Given that all work is happening in the database, I don’t need much RAM or compute on these functions. If folks are interested in doing something similar, comment below and I will share an example.

Closing Thoughts

There is a lot of value in having data quality checks consistently running on your datasets. Even having a simple check on row counts can go a long way. Applications can appear to be performing fine, as your logs or existing error monitoring solutions aren’t flagging anything. Only by inspecting the underlying data can the true issues be uncovered. With a small amount of upfront investment, ge gives you a powerful framework for executing continuous data quality checks to help you reveal such issues.

The code I outlined above is enough to get you started with a simple ge deployment. In a future post I will dive into using the other functionality provided by ge to support more advanced deployments, involving scaling up to support execution of multiple sets of expectations along with custom alerting and reporting.